Good evening everyone,

|

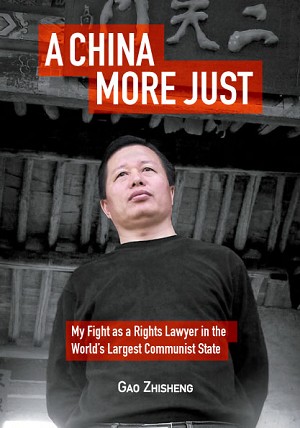

Gao Zhisheng (Broad Press)

|

I am honored to be here introducing you to Gao and to the book.

As I was thinking about how to begin tonight, I asked myself – what would Gao say if he were here tonight? He would probably say – ‘why are you making such a fuss over me? This book is about the people in China who are suffering; they are the real heroes.’

It is this voice of humility and compassion, as well as fearlessness, that comes through in Gao’s writing and leaves a deep impression.

His style of writing is also quite noticeable. Gao often uses direct quotations from the people he has interviewed. So, I’m going to modestly follow his lead and read several excerpts as part of my talk this evening.

As someone who was more familiar with his recent activism, one of the most fascinating aspects of this book was learning about Gao’s personal background.

He was born in 1964 in rural Shaanxi province and grew up in his mother’s cave dwelling. He had six brothers and sisters and he writes about how they often did not have enough food to eat.

In this context, his mother’s kindness to strangers clearly left a strong impression on him, a tradition he has continued in his human rights work.

In the first chapter of the book he describes his mother as follows:

“My mother was a person of great moral strength. Yet her moral strength cannot be fully captured by the pen in my hand, nor even fully fathomed by my mind. It was something in her that deepened over the course of an entire lifetime….” (28)

“A woman beggar with a child came to our place. As it happened, though, we ourselves had nothing to eat at that time and were in no position to offer her anything. The woman was quite disappointed. She took her child’s hand and began to leave. My mother then told her to wait for a moment. Soon my mother came back with two corn cobs that weren’t quite ripe. It turned out that our other had gone to the family plot and broken off the cobs for the woman.” (30)

Coming from this background, Gao then joined the army for several years and after his dismissal, he sold vegetables in rural Xinjiang Province. It was while doing this that one day he saw an advert in a newspaper that China was seeking to train lawyers. So, with just a middle school education, he decided to learn. He managed to teach himself law and passed the bar exam in 1995 on his first try.

Four years later, he became known nationwide for winning the largest medical malpractice suit in Chinese history for a young boy who had lost his hearing. At the time, Gao was the only lawyer in China who agreed to take the case pro bono.

In 2001, he was named one of China’s top ten lawyers following a legal debate competition sponsored by the Ministry of Justice.

Since then he has worked for the gamut of China’s vulnerable groupscoal miners, petitioners, home-demolition victims, villagers fighting election fraud, and house church members. In fact, he himself is a Christian.

You can sense his indignation at the unnecessary suffering by these groups from his writing.

“A few days ago, as some sixty Shanghai residents who had petitioned the government were leaving my office, I was so pained and couldn’t help shedding tears as I watched their figures recede into the bitter cold. It took me a long time to calm down, and sad scenes kept flashing through my mind. I saw the feeling of helplessness in the eyes of Du Yangming, an older man, and in his trembling hands as he tried to button up his thick coat when leaving my office. I thought about the adverse circumstances they were facing in the severe winter and about how they might be arrested at any moment…

Of these sixty or so men and women, only three or four hadn’t been subjected to illegal forced labor; the rest had all suffered this cruel form of treatment at the hands of the Shanghai ‘people’s’ government.” (93)

In dealing with all of these causes, one can see his fearlessness and willingness to take on the most sensitive issues in Chinese society. His work for the Falun Gong spiritual group is perhaps the clearest example of this.

For those who aren’t familiar with it, Falun Gong is a spiritual and meditation discipline that the Party banned in 1999 despite its popularity and indeed, according to many, because of its popularity, which was deemed to be a threat to the Communist Party’s hold on power.

The Party then unleashed a brutal and systematic persecution that has included sentencing hundreds of thousands of innocent people to labor camps without trial. It has also included orders to lawyers not to take Falun Gong cases.

In this way, Falun Gong has arguably become the number one taboo in Chinese society. It is one of those issues over which one simply cannot voice disagreement with the Party’s policy.

It was in this context that in 2004, Gao was one of the first lawyers to break that taboo.

He was hired by an adherent who had been sentenced illegally to a labor camp and so Gao tried to file for judicial review. He writes about visiting multiple courts in one day and being told by three judges: “Don’t you know we don’t take Falun Gong cases?”

With these legal avenues closed, Gao decided to write an open letter to the National People’s Congress and a few months later, he conducted the first of two in depth investigations into the persecution of Falun Gong.

Following these investigations, in October and December 2005, he then wrote two open letters to China’s top leaders, detailing the torture he had uncovered and urging them to end the atrocities.

I’ll just read a few sections from the second of these letters. I hope you can keep in mind the fact that the group he is talking about is an oppressed religious minority about whom no one prominent in China had dared to publicly say a sympathetic word for six years.

“With a trembling heart and a trembling pen, I record the tragic experiences of those who have been persecuted in the last six years. Of all the true accounts of incredible violence that I have heard, of all the records of the government’s inhuman torture of its own people, what has shaken me most is the routine practice on the part of the 6-10 Office and the police of assaulting women’s genitals…Almost all who have been persecuted, be they male or female, were stripped naked before being tortured. No words can describe our government’s vulgarity and immorality. Who, that can rightly be called a human being, could possibly stay silent in the face of these facts?” (137)

“Wang Yuhuan is a Falun Gong believer who was arrested in Changchun and has been in and out of jails and labor camps a total of nine times. She recalled the following: ‘They tied me up with rope and put me in the trunk of a police car. They drove to a mountain….Twenty-three practitioners were tortured to death there. I knew many of them. The police simply buried their bodies in a pit. After Xiang Min, a nice-looking woman, came back from being tortured, she told me that the policemen assaulted her by groping and electrocuting her at the same time.

It took over two hours for them to drive me to that devil’s den in a mountain. I heard them stop the car…They dragged me along and banged me against trees as they took me to a building... One of the police said, ‘Let’s wait and see how you die today. Nobody has come out of here alive!’…I saw a tiger bench and many policemen busily preparing to torture me. A few policemen forced me onto the tiger bench…They started a round of torture every five minutes.” (146-148)

“It is time for the government to fess up. I would like to stress that if this evil crime does not stop, then the day when Chinese society is stable and harmonious will never come… meanwhile, in communicating with people of such conviction, I saw them demonstrate qualities invaluable to our nation. The fact that they were able to describe their horrible experiences with a pleasant countenance and a calm tone of voice left a deep impression. I found myself moved to tears. I am finally seeing people in this country with an unyielding spirit and a resolve to protect something dear to their souls. These six years of persecution have fashioned a group of people unparalleled in character. The realm of mind they demonstrate through the solidity of their faith, their contempt for the atrocities they endure, and their optimism about our nation’s future has earned my deepest respect.” (156)

It’s evident from his letters that Gao had hoped that once the top leaders discovered what was happening at local levels, they too would be outraged and act to stop it

But instead, he found the system turned against him. Within days of the publication of his first open letter, he came under 24-hour surveillance by plainclothes police. A few weeks later, his firm was shut down and his license to practice law was revoked. The following month, there was attempt on his life when a military vehicle tried to run him over.

Rather than recoiling, Gao’s reaction was increasing disillusionment with the regime and fearless defiance.

He thus did three things:

First, he publicly quit the Party on what he called “the proudest day of my life.” In this way, he joined millions of other Chinese who have announced their withdrawal from the Party in recent years. Many of them have used aliases, however. Gao’s use of his real name was quite unusual.

Moreover, despite the risks he soon began urging others to also quit the Party.

“Let’s each begin doing something useful in our own area—let’s use every possible means to encourage people to publicly withdraw from this murderous clique, to no longer help the murderers do evil, and to no longer be used as the murderers’ tools! Let us peacefully put this murderous clique to an end by severing our ties to the Chinese Communist Party! Let’s completely free ourselves from this disastrous misfortune!” (103)

The second thing that Gao did was publish a daily online journal, exposing the authorities’ persecution of him and his family. Thus, when five police cars were outside his home, he posted it online. When he was detained and interrogated, he posted it online. When police followed his 12-year-old daughter to school everyday, he posted it online.

Even when they cut off his phone, disconnected his internet and arrested those who came to visit him, he just picked up his mobile phone and dictated his journal to other activists who would post it online.

The third thing he did was that starting in February 2006, he managed to rally China’s activists and legal community in what was one of the most significant grassroots mobilizations in China in recent years. He launched a relay hunger strike for human rights in which each participant would fast for 24 hours before passing the strike to the next person. The effort drew participants from 29 provinces, as well as dissidents abroad.

It is at this point that the book ends because the Chinese edition was published in May 2006. But since many of you are probably asking what his situation is now, I wanted to spend a few moments talking about what has happened since.

In August 2006, Gao was abducted without a warrant while visiting his sister in rural China. He was held in incommunicado detention for nearly four months. During that time, his wife and 12-year-old daughter were beaten up by police and he was tortured.

In December 2006, he was sentenced in a one day trial to three years in prison. But this was suspended, thanks in large part to the international support he had received, including an urgent action by Amnesty International, and open letters from Human Rights Watch and the Human Rights Law Foundation.

Up until a few weeks ago, he remained under house arrest, with limited ability to communicate to the outside world and mostly taking time to physically recover from the torture he had endured in custody. Then, in mid-September he wrote an open letter to U.S. Congress detailing a range of recent abuses and asking the U.S. government to boycott the Olympics. The day after the letter’s publication, he was abducted from his home and hasn’t been heard from since.

I hope this has given you an idea of who Gao is and what he is fighting for. I’d like to finish with something that Canadian lawyer David Matas said about Gao at a recent ceremony where he was awarded a Courageous advocacy award.

To me it summarizes who he is and why I felt that editing and reading this book was most of all a learning experience, not just as someone wanting to understand grassroots developments in China but as a person. It has also taken on that much more meaning given his recent actions and abduction.

“What was stunning about Gao is not so much that he has stood up for justice and the rule of law, as admirable as that is, nor that he was persecuted for it, as deplorable as that is. It is rather that he stood his ground as the persecution accumulated, as it accelerated. He could not help but know that what he was doing was going to bring disaster on him; but he did it anyways. We all hope never to be in the situation in which Gao Zhisheng has found himself. But we also have to hope that if we do, we would act as he has done.”

NTDTV Asia Talk: Sarah Cook on Gao Zhisheng's book A China More Just:

|

|

Sarah Cook holds an LLM in Public International Law from the University of London and has served as an NGO delegate on Chinese torture cases to the United Nations Human Rights Commission. She is co-editor of the English version of A China More Just. |